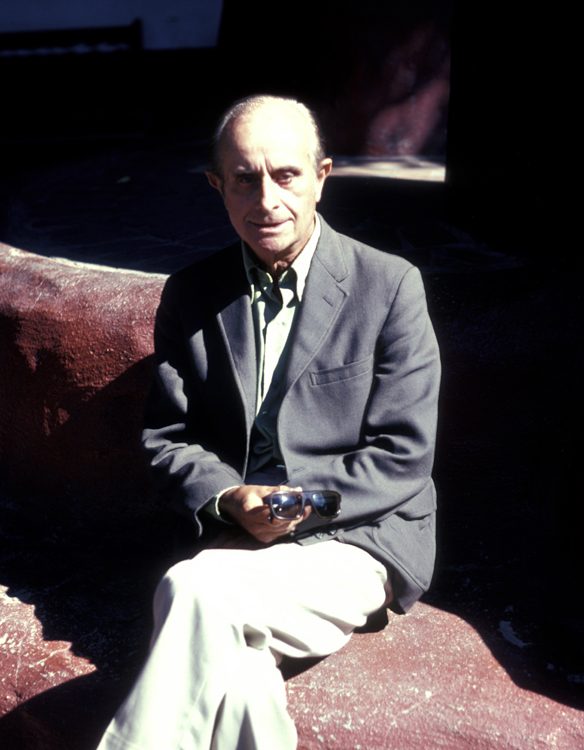

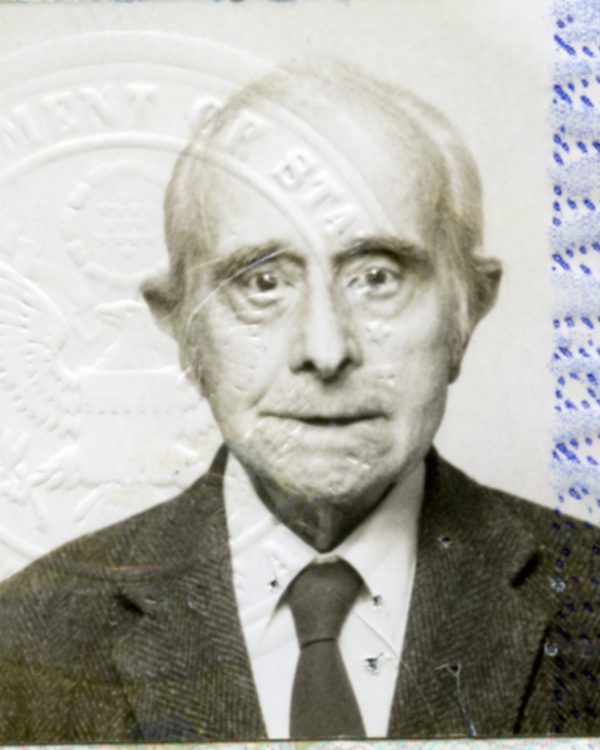

Biography

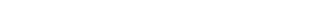

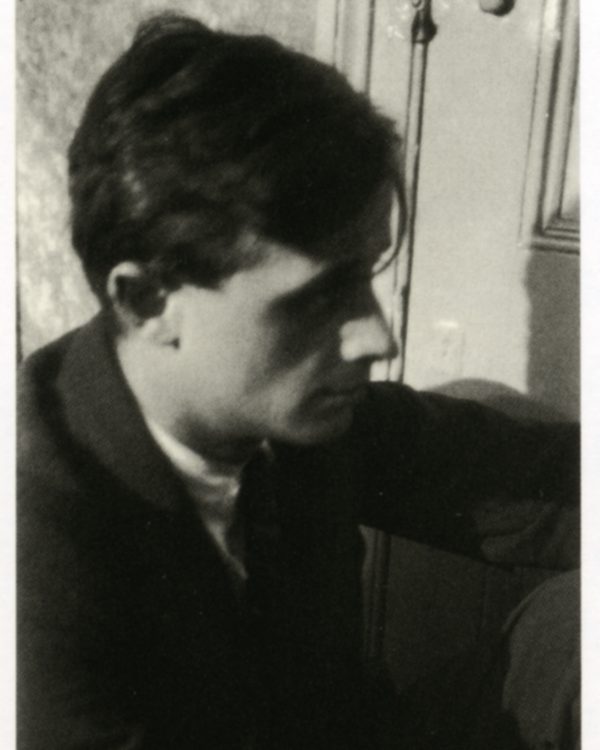

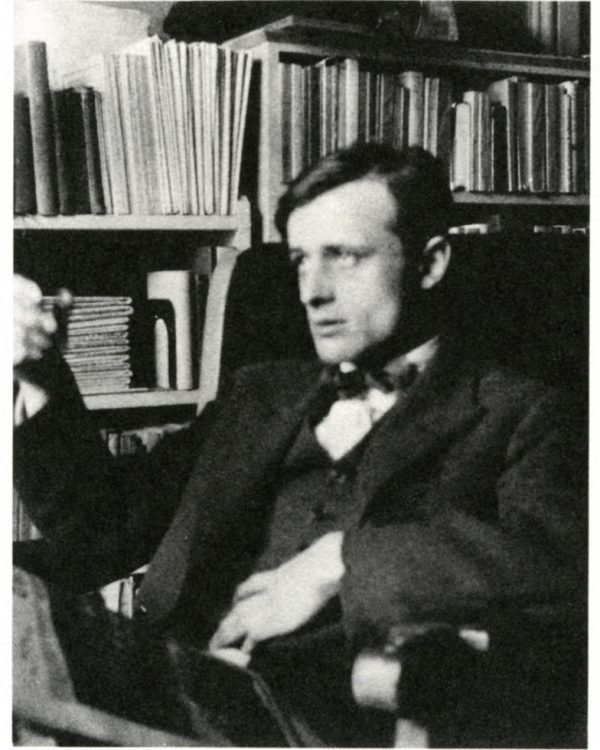

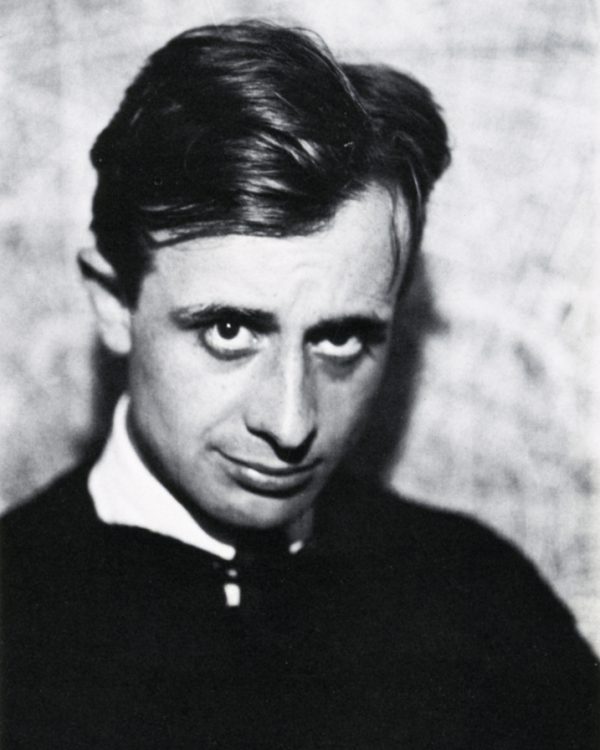

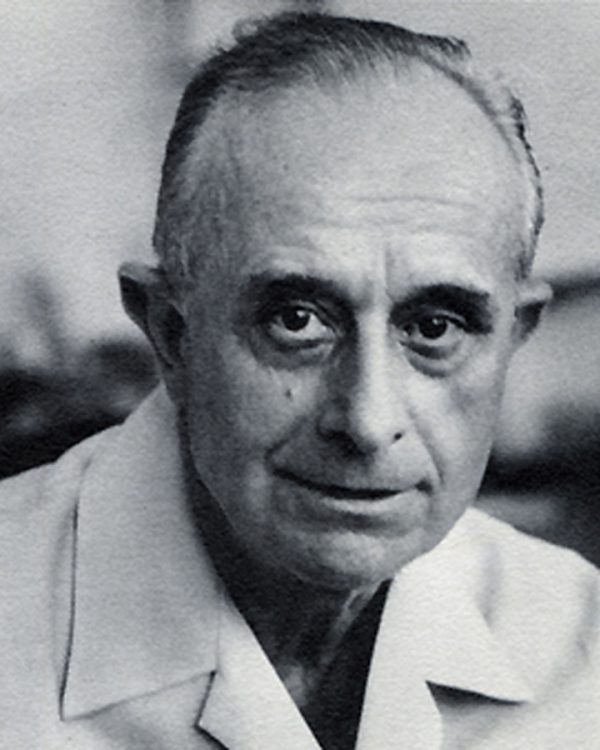

Johannes (Hanns) Skolle was born in 1903 in Plauen, Germany, and was brought up in a circus in Czech Bohemia. After studying at the KunstAkademie in Leipzig, his future in post-war Germany looked uncertain. That was when an uncle unexpectedly appeared in his life and played his destiny by tossing a coin in the air. Heads : New York ; tails : Buenos Aires. In May 1923 they arrived in New York. His uncle gave him 120 dollars and a piece of advice : “Now, get a job”. Hanns was 20.

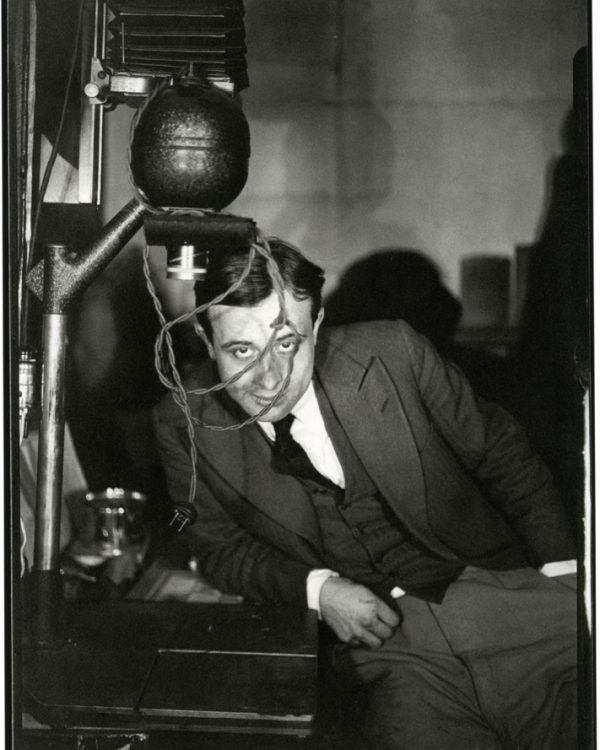

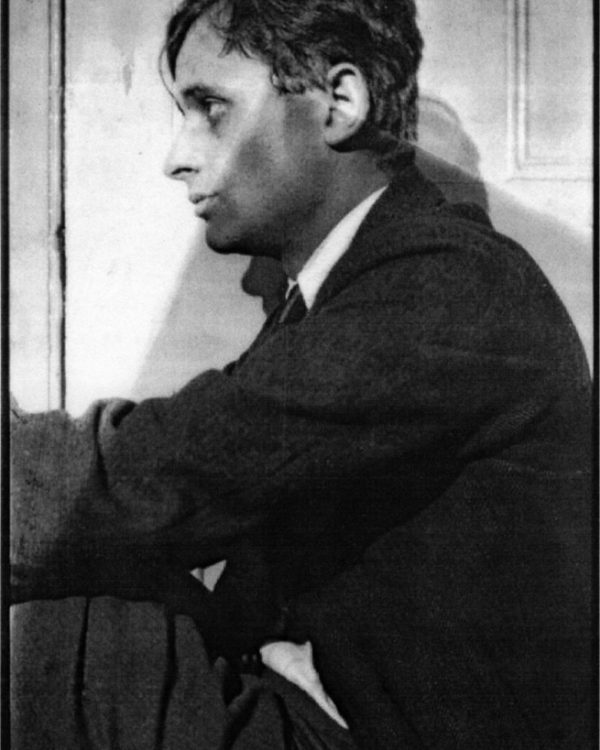

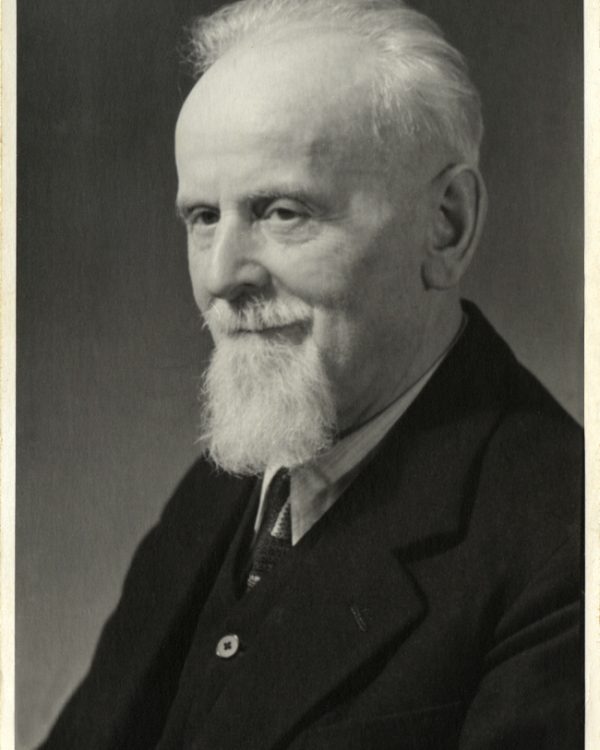

In Brooklyn and Manhattan, where he lived, he studied at the Art Students League, and soon made friends : the poet Hart Crane, the screenwriter Ben Hecht, the photographer Walker Evans, with whom he shared an apartment…

He married a young woman who had recently immigrated from France, Elisabeth (Lil), and became the father of a daughter, Anita, in 1927. But the couple parted and John started travelling in Europe and North Africa.

In Paris, Amsterdam and on the French Riviera he worked for fashion houses, publishers and magazines and met Picabia, Giacometti, Pascin, Noguchi, Van Dongen, Hilaire Hiler, Picasso and the film-score composer Georges Antheil.

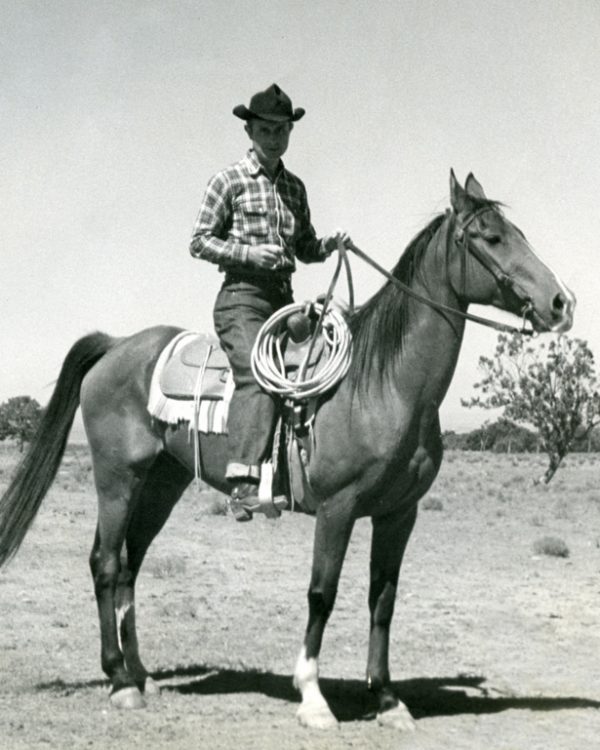

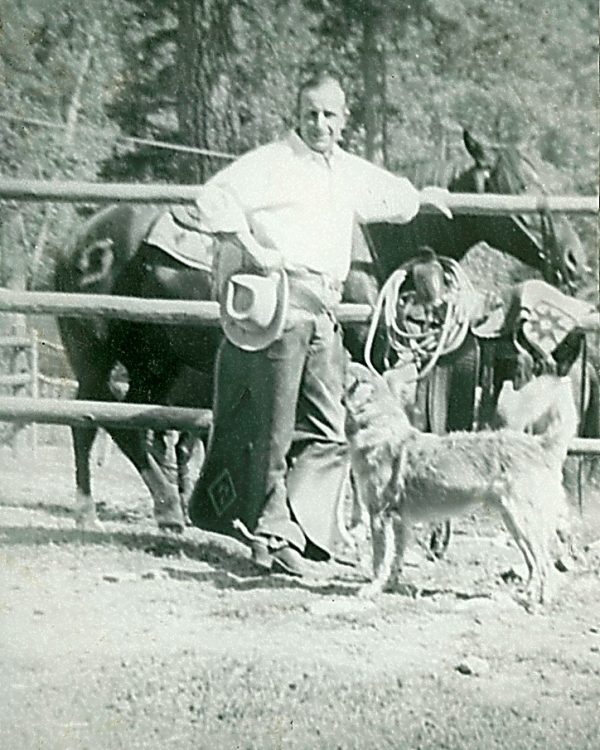

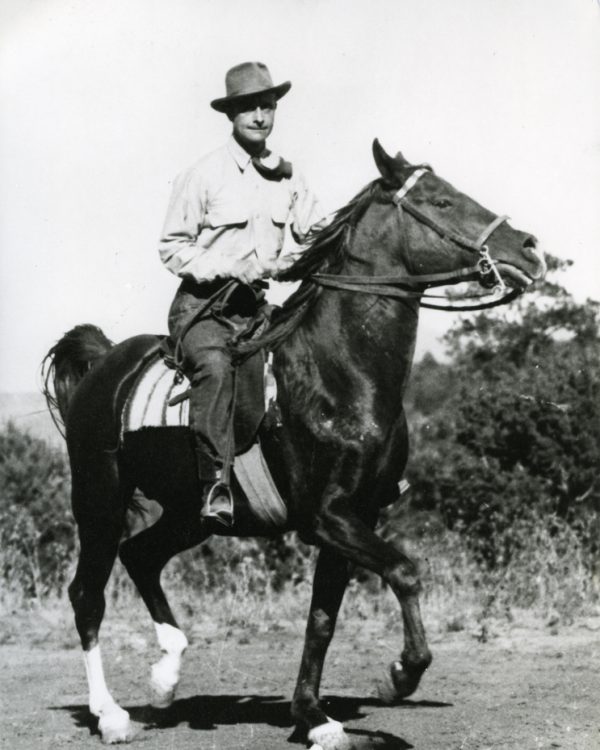

Back in the U.S. in 1939, he moved west and worked on ranches in charge of horses before becoming an art teacher. In Arizona he met the architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

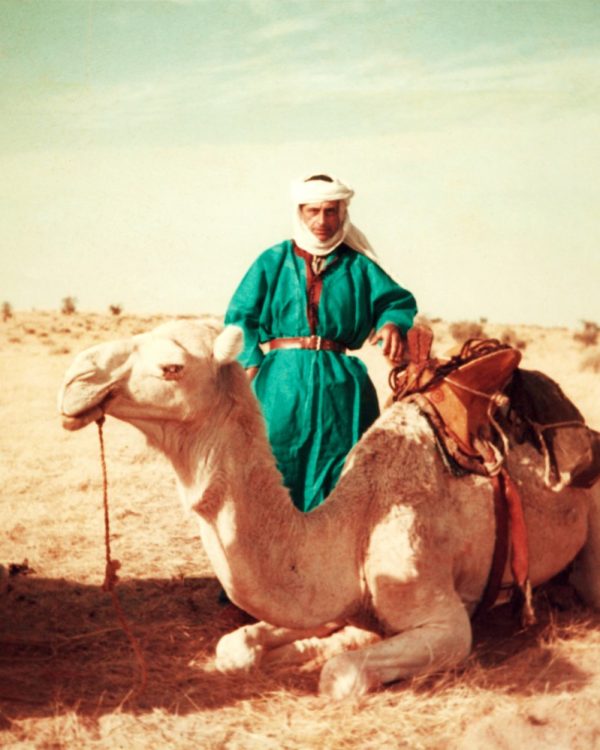

In the 1950s, he went back to the Sahara and crossed part of it with a caravan of Tuareg tribesmen. The account of his trek – Azalaï – was published in 1956, in the U.S., Great Britain and Japan. The book is still around and can be found half a century later. John Skolle befriended the Hollywood actor Peter Lawford (who was Marilyn Monroe's friend, President Kennedy’s brother-in-law and a member of Frank Sinatra’s Rat Pack).

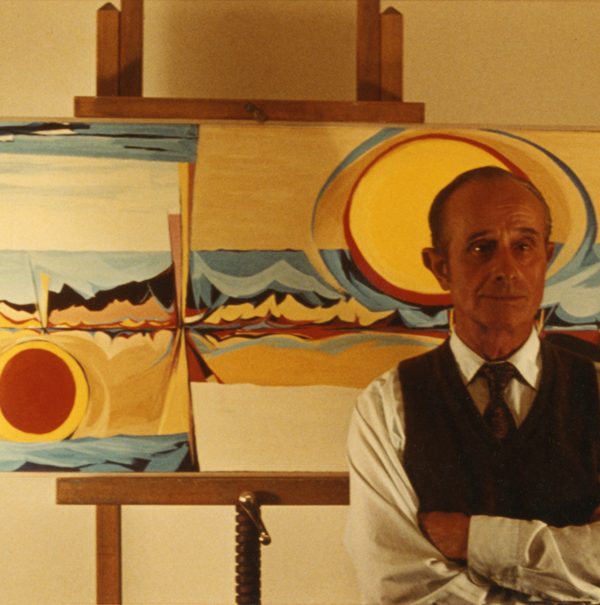

In the 60s and 70s, John Skolle mostly travelled to Africa and Central America, where he found inspiration both in art and ethnography. He eventually became Associate Director of the Department of Art at the University of New Mexico. He published a monography on the Seri Indians of Sonora, Mexico and wrote his biography in the 1980s – Biography of a Double.

John Skolle’s paintings were shown and kept in many American museums such as the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe, the Denver Art Museum, the Jonson Gallery at UNM in Albuquerque, the Wurlitzer Foundation in Taos, the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the National Gallery in Washington, the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh, the Santa Barbara Art Museum, the Seattle Art Museum, at Princeton University, and at the Bonestell Gallery in New York, as well as in many private collections throughout the world. John Skolle was awarded a number of prizes in New Mexico and California for his artistic achievements.

In the last few years, John Skolle’s works have been auctioned and have obtained high ratings.

The Skolle family archives related to Walker Evans are kept at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and at Yale University. They include paintings and photographs of/by Hanns Skolle (John) and Walker Evans, and correspondence between Evans and Hanns or Lil Skolle. Many portraits of Hanns Skolle (and his wife and child) made by Walker Evans appear in recent publications, along with the detailed account of the whole relationship between Skolle and Evans in New York and Connecticut between 1926 and 1934. It is widely admitted that John Skolle exerted a strong influence on Walker Evans, thus enabling the photographer to develop his talent and reach recognition then fame.

John Skolle always refused compromises that would allow him to promote his own name and creation. Total freedom of thought and speech was more valuable in his eyes than artificially creating a legend for himself.

Among other feats, John Skolle slept with a rattlesnake in his tent and was attacked by sea-eagles in the desert of Sonora, Mexico ; he accidentally drank kerosene at a party and swallowed ground glass and insects served at a dinner during the Mau Mau uprising in South Africa – and had to travel by ship from Cape Town back to England to get treatment. But it was solitude, old age and disillusionment that eventually killed him on Christmas Day of 1988. He was almost 86.